The final paper of my PhD thesis has just been published online in the journal Scientific Reports. The paper, titled “Behavioural and pathomorphological impacts of flash photography on benthic fishes” explains the effects of typical diver behaviour while photographing small critters such as seahorses or frogfishes.

The paper itself can be a tad technical, so with the help of two co-authors (Dr. Ben Saunders and Tanika Shalders), I wrote this summary of the research, which was published first at The Conversation (original article here).

We all enjoy watching animals, whether they’re our own pets, birds in the garden, or elephants on a safari during our holidays. People take pictures during many of these wildlife encounters, but not all of these photographic episodes are harmless.

There is no shortage of stories where the quest for the perfect animal picture results in wildlife harassment. Just taking photos is believed to cause harm in some cases – flash photography is banned in many aquariums as a result.

But it’s not always clear how bright camera flashes affect eyes that are so different from our own. Our latest research, published in Nature Scientific Reports, shows that flash photography does not damage the eyes of seahorses, but touching seahorses and other fish can alter their behaviour.

Look but don’t touch

In the ocean it is often easier to get close to your subject than on land. Slow-moving species such as seahorses rely on camouflage rather than flight responses. This makes it very easy for divers to approach within touching distance of the animals.

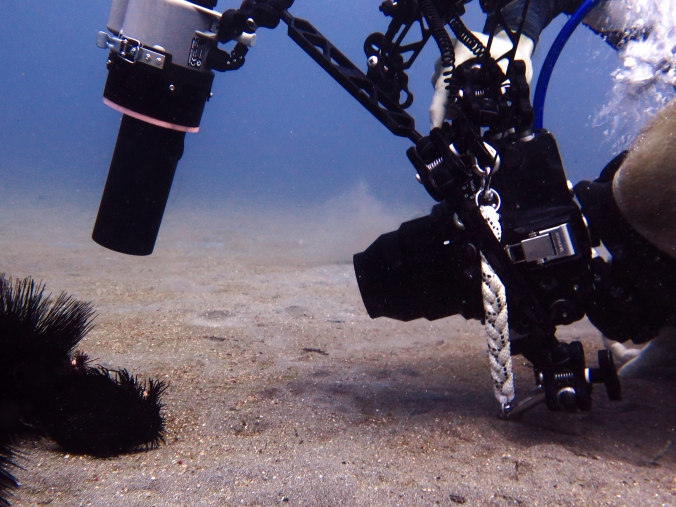

Previous research has shown that many divers cannot resist touching animals to encourage them to move so as to get a better shot. Additionally, the high-powered strobes used by keen underwater photographers frequently raise questions about the welfare of the animal being photographed. Do they cause eye damage or even blindness?

Does flash harm fishes? Photo: Luke Gordon

Aquariums all around the world have taken well-meaning precautionary action. Most of us will have seen the signs that prohibit the use of flash photography.

Similarly, a variety of guidelines and laws exist in the scuba-diving community. In the United Kingdom, flash photography is prohibited around seahorses. Dive centres around the world have guidelines that include prohibiting flash or limiting the number of flashes per fish.

While all these guidelines are well-intended, none are based on scientific research. Proof of any damage is lacking. Our research investigated the effects of flash photography on slow-moving fish using three different experiments.

What our research found

During the first experiment we tested how different fish react to the typical behaviour of scuba-diving photographers. The results showed very clearly that touching has a very strong effect on seahorses, frogfishes and ghost pipefishes. The fish moved much more, either by turning away from the diver, or by swimming away to escape the poorly behaving divers. Flash photography, on the other hand, had no more effect than the presence of a diver simply watching the fishes.

For slow-moving fishes, every extra movement they make means a huge expense of energy. In the wild, seahorses need to hunt almost non-stop due to their primitive digestive system, so frequent interruptions by divers could lead to chronic stress or malnutrition.

The goal of the second experiment was to test how seahorses react to flash without humans present. To do this we kept 36 West Australian seahorses (Hippocampus subelongatus) in the aquarium facility at Curtin University. During the experiment we fed the seahorses with artemia (“sea monkeys”) and tested for changes in their behaviour, including how successful seahorses were at catching their prey while being flashed with underwater camera strobes.

The aquaria were the seahorses were housed during the experiment

An important caveat to this experiment: the underwater strobes we used were much stronger than the flashes of normal cameras or phones. The strobes were used at maximum strength, which is not usually done while photographing small animals at close range. So our results represent a worst-case scenario that is unlikely to happen in the real world.

West Australian seahorses (Hippocampus subelongatus) in their aquarium at Curtin University

The conclusive, yet somewhat surprising, result of this experiment was that even the highest flash treatment did not affect the feeding success of the seahorses. “Unflashed” seahorses spent just as much time hunting and catching prey as the flashed seahorses. These results are important, as they show that flashing a seahorse is not likely to change the short-term hunting success (or food intake) of seahorses.

We only observed a difference in the highest flash treatment (four flashes per minute, for ten minutes). Seahorses in this group spent less time resting and sometimes showed “startled” reactions. These reactions looked like the start of an escape reaction, but since the seahorses were in an aquarium, escape was impossible. In the ocean or a large aquarium seahorses would simply move away, which would end the disturbance.

Our last experiment tested if seahorses indeed “go blind” by being exposed to strong flashes. In scientific lingo: we tested if flash photography caused any “pathomorphological” impacts. To do this we euthanised (following strict ethical protocols) some of the unflashed and highly flashed seahorses from the previous experiments. The eyes of the seahorses were then investigated to look for any potential damage.

The results? We found no effects in any of the variables we tested. After more than 4,600 flashes, we can confidently say that the seahorses in our experiments suffered no negative consequences to their visual system.

What this means for scuba divers

A potential explanation as to why flash has no negative impact is the ripple effect caused by sunlight focusing through waves or wavelets on a sunny day. These bands of light are of a very short duration, but very high intensity (up to 100 times stronger than without the ripple effect). Fish living in such conditions would have evolved to deal with such rapidly changing light conditions.

This of course raises the question: would our results be the same for deep-water species? That’s a question for another study, perhaps.

So what does this mean for aquariums and scuba diving? We really should focus on not touching animals, rather than worrying about the flash.

Flash photography does not make seahorses blind or stop them from catching their prey. The strobes we used had a higher intensity than those usually used by aquarium visitors or divers, so it is highly unlikely that normal flashes will cause any damage. Touching, on the other hand, has a big effect on the well-being of marine life, so scuba divers should always keep their hands to themselves.

Look, take pictures, but don’t touch!

NOTE: I realise that this is a controversial topic in underwater photography. If you have relevant questions, comments, or thoughts you want to share, feel free to add them in the comment section below. If you are interested, I would highly advise you to read the original research paper via this link. The paper is open access, so anyone can read and download it. If you have specific questions about the paper, you can always contact me via email here.

There has been an outbreak of common sense (perhaps informed by your research) in the UK and the Marine Management Organisation have ‘softened’ their advice on flash photography of seahorses to ‘minimise’ use of flash. The ‘no effect’ conclusion was what a well-known amateur naturalist always insisted was the case for seahorses in Studland Bay (southern England) but folks sitting in offices and making regulations are often badly advised by well-meaning but misguided individuals and ignore experienced if ‘unqualified’ folks.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment Keith. I guess it’s better to be too cautious than not cautious enough and regretting it later…but if all available evidence indicates that there are other things that are more pressing to worry about, it only makes sense to adapt to these facts

LikeLike

Glad to have found a scientific study on this matter. Do you know anything about the effect of flash in larger marine life? I am mostly interested in sea turtles.

Thank you!

Kostas

LikeLike

Hi Kostas, thanks for asking. Very little work has been done on larger animals, and I don’t know of any on sea turtles. I would hypothesize that since they live on the interface between water and air,their visual systems would be quite well adapted to quickly changing light intensity. Though this would of course have to be tested. In my humble opinion, i think the bigger issues for turtles would be people getting to close / touching,which might result in fatigue,stress,… or even issues coming up for breathing.

LikeLike

I haven’t read the full artule however the statement “Flash photography does not make seahorses blind or stop them from catching their prey.” Needs to be removed! Its very speculative and not scientific, your study indicates that in the individuals you tested of one species of seahorse (Hippocampus subelongatus), no adverse optical damage or feeding behaviours were observed. I assume the flash was done in the water using a subsea flash housing rather than outside a glaas aquarium where a vast majority of light is reflected? I can tell you that in the UK which experiences higher turbidity/lower visability species such as H. guttulatus can die from single flash photography, even in an aquarium setting, I and colleuges have seen it happen. There’s no smoke without fire to these bans, please remove your potentially damaging comment which implies people can ignore otherwise sound advice of no flash photography. Thanks

LikeLike

Hi James, I would strongly recommend you to attentively read the full research paper before making strong statements about the quality of the science or the conclusions me and my coauthors have drawn.

I can assure you the design was designed with the utmost care, and if you had read the research,you would know that we used multiple species of seahorses, frogfishes,and ghostpipefishes.

If you had read the paper you would know that we used both aquarium and underwater experiments,which all clearly indicated the same results.

The species used in the aquarium study (H. subelongatus) lives in turbid environments, often in visibility less than 2m.

The bans currently in place in many locations are based on the precautionary principle, not on actual science. This is even acknowledged in the report that banned seahorse flash photography published by the UK government.

Lastly, both the paper and other publications me and my coauthors wrote on the topic clearly state the importance of ethical photographer behaviour and that touching animals should be avoided at all cost.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Artigo publicado sobre os efeitos do impacto do uso de flash subaquático na vida marinha – DIVEMAG.com Sua revista de mergulho

Pingback: Photo sous-marine: les flashs dérangent t-ils les poissons ?

So you killed Seahorses to test if you harmed them?? 🤔

LikeLike

Not entirely, I did euthanize a few seahorses to test if their visual systems were damaged. Unfortunately there is no other way to test this. I didn’t like this, but the alternative was not to run the experiment and have the myths of the effects of flash photography continue for years.

LikeLike

Maarten, if I understand this right the flashes emulated UW photography, how about the use lights for videos, which are not used for seconds but much longer periods ?

LikeLike

I did not test the use of video lights (logistics + cost issues). From experience i can say 2 things:

1) It is very unlikely to cause pathomorphological damage. The light is not strong and focused enough + the water diffuses the light very strongly

2) Marine life seems to react stronger to intense video lights, so it potentially causes more stress. I would advise to see how the animal reacts and turn off the lights if it appears stressed.

LikeLike

Wow, this is really interesting and actually completely the opposite of what we were led to believe. Have there been other tests to confirm your findings?

LikeLike

Hi Emma,

This is the first study that did it in a much detail and with the specific focus on effects of scuba flash during fun dives. There have been a number of other studies on effects of flash on a range of fishes in aquaria and in the wild, none of them found a negative effect from the flash…

LikeLike

I’ve read this paper before and just realized that the author is you! Depending on your work, I can defend myself from criticism about using strobe underwater. I am a diving instructor & marine biologist and I also told my divers that physical manipulation is the worst for marine life. Your work is something we can teach people how we should behave in diving. I look forward to seeing more research articles from you. Good job it is on NATURE. (clap)

LikeLike

Glad you like the paper, but even happier you’ve used it while teaching dive courses! Keep an eye on the blog for new research updates 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great website to use for studying! My teacher told my class to study impacts on our world so I decided to study marine littering! Thank you so much for being able to create such a useful and helpful website!

LikeLike

Hi Olivia, sorry for the very slow reply. Thanks for your kind words, I’m glad you like the website! Maybe I should do a post on marine littering soon?

LikeLike

When creatures such as seahorses and frogfish swim away when approached by divers, they’ve clearly been over-loved. I’ve been guiding divers on Bonaire since 1982, My program is Touch the Sea but we don’t touch or handle seahorses and frogfish, for example, because they don’t like it. They don’t like flash photography either. If a frogfish twitches every single time a flash goes off, no matter the condition of its eyes, that’s a pretty good indication that the flash disturbs the froggie. Perhaps you should broaden your search for signs of discomfort.

LikeLike

Hi Dee, thanks for your comment. You are definitely right about some animals being over-loved. We did look at other signs of discomfort, if you are interested, I’d advise you to go beyond the blogpost and read the full research paper which has all those details 🙂 Frogfish (and other fishes) might behave different depending on the species (which was the case to some extent in this study) or even the amount of divers that regularly visit the area.

LikeLike

Hi I’ve just come across your report. I’m going to link it into my study concerning ethics in wildlife photography. I noticed in some articles that there is a ban on the use of flash photography in the U.K. is this true and where can I locate more information about this law/regulating?

LikeLike

Hi Jon, sorry for the very late reply! If you’re still interest, here is the original MMO report, which states that there is no proof for damage, but still advises the ban: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20140305103938mp_/http://www.marinemanagement.org.uk/evidence/documents/1005b.pdf

LikeLike