During my PhD I have written and talked a lot about the value of scuba diving and particularly of muck diving. Dive tourism often provides an income to communities who have limited sustainable alternatives to make a living. Over the last years, there have been big changes in dive tourism, such as the increasing popularity of underwater photography. Muck diving in particular has a large portion of divers who use underwater cameras: I found out that on average 73% of people visiting muck dive destinations use a camera of some sort.

More people using cameras underwater can be a good thing. Photographers often spend more time and money in dive locations, meaning a higher income for local communities. Having a lot of photos taken underwater can directly help science by giving us information about species distribution (via initiatives like iSeahorse) or even by helping researchers discover new species (the story of the “Lembeh Seadragon“). Finally, more beautiful photos of ocean critters can help conservation by creating awareness with people who would otherwise never go near the ocean.

The “Lembeh Seadragon” (Kyonemichthys rumengani) was first brought to the attention of scientists by underwater photographers. Photo: Maarten De Brauwer

However, there are some serious issues with the use of cameras under water. Using an extra tool while diving is distracting and often leads to poor buoyancy control. Multiple studies have looked at the effects of divers who use cameras on coral reefs, and it is very clear that photographers cause more damage on coral reefs than divers without cameras. Possible solutions for this problem include buoyancy training, good dive briefings that create awareness with the divers, and attentive dive guides who can adjust diver behaviour before too much damage is done.

Source: Dive Photo Guide

Another problem with underwater photography is that it is a goal-driven and therefore often competitive activity. Photographers want to see rare species, shoot interesting behaviour or get a unique shot that will impress fellow divers in off- and online communities. But the reality is that rare species are hard to find and often really shy. You have to be lucky to observe eye-catching behaviour and it takes a lot of skill to get creative shots underwater. The desire for beautiful pictures too often leads to divers trying to “force” a photo to happen, and forcing wildlife is never a good idea.

This is not just an issue with underwater photography, it happens on land as well. In 2010 a Wildlife photographer of the year lost his title when it became clear he faked his winning shot. In India, the bad behaviour of tourists trying to take pictures of tigers has led to the creation of a guidebook for ethical wildlife photography. There are worse stories out there and this article explains just how bad “getting that perfect shot” can get.

Underwater wildlife photography has its own specific problems. Unlike terrestrial photography, divers can often get within touching distance of the species they want to photograph. At that point it is often very difficult to resist the temptation not to touch or harass the animal. There are many reasons why you shouldn’t, and you’ll find most of them explained clearly here. Luckily most fish, especially the bigger species like sharks or manta rays can swim off when things get too crazy, but this doesn’t work for all ocean critters.

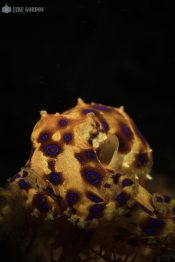

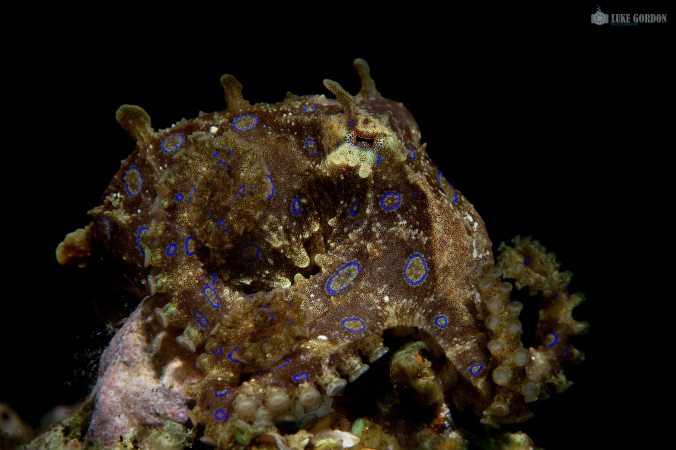

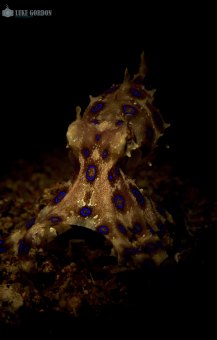

Animals that cannot swim away because they are too slow or rely on camouflage instead of speed, are popular with photographers because you can take your time for a picture. Frogfishes, seahorses, nudibranchs, scorpionfishes … never had to cope with humans and cameras, so they don’t have any defence against them. Some of the poor diver behaviour I have seen seems relatively harmless, like gently coaxing an animal in a better position. But it can go as far as smacking Rhinopias around to daze them so they will sit still, pulling of arms of feather stars to get pictures of the fish living inside them, or breaking off seafans with pygmy seahorses on them and bringing them up to shallow water so divers can spend more time taking pictures. In these extreme cases, diver behaviour can lead to serious harm or even the death of rare animals.

Pictures of interesting behaviour like this yawning frogfish (Antennarius commersoni) are popular, but the yawn might actually be a sign of distress.

To a large extent it remains unknown what the effects of diver manipulation are, though it is clear to see that it at the very least stresses animals. I am currently working on a project to find out which negative diver behaviours around critters are most common and how it effects the animals. The goal is to enable the dive industry to focus on preventing the behaviours which have the highest impact.

While most divers don’t approve of this unethical behaviour, industry leaders like organisers of photo competitions or dive centres still seem reluctant to admit there are serious ethical issues in underwater photography. Maybe out of fear of giving underwater photography a bad name, or out of fear to make less profit when strict rules are applied. What we need is a change in mentality from divers and industry leaders. Well known photographers like Dr. Alex Tattersall and Josef Litt are increasingly making themselves heard to set the right example. Organisations like Greenfins work closely with dive operators to improve destructive dive practices. A lot of this unethical behaviour can and will disappear with the support of divecentres, dive magazines and role models from the underwater photography community. So if you enjoy taking pictures underwater, consider signing this petition that asks for higher ethical standards in dive magazines and photo competitions.