As I mentioned in an earlier post, my research in Indonesia would not be possible without the help of local counterparts. I work with some excellent people at Universitas Hasanuddin in Makassar, Sulawesi.

Last week I was invited to teach a lecture about the research I have been doing so far. The idea was to share ideas with local researchers and to suggest potential areas of research for students at the faculty of marine science and fisheries. I was honoured to get such an invitation. As a researcher you are often working on your little island (often literally in my case) and we sometimes forget that sharing knowledge should be the ultimate goal of doing your research.

I feel this is even more important when working in countries like Indonesia. Places which are rich in biodiversity and natural resources, but often lack the infrastructure and resources to protect it in a way that benefits the local people. Over the last years I have met many very motivated and talented researchers, but all too often they do not have the resources to reach their full potential. Things that seem simple for those of us fortunate enough to be based in a first world country often are complicated for those who don’t. Whether it’s attending international conferences to stay up to date with what is new and network with other researchers, buying good quality equipment to do your research or writing scientific papers in a language that is very different to your own…

I feel this is even more important when working in countries like Indonesia. Places which are rich in biodiversity and natural resources, but often lack the infrastructure and resources to protect it in a way that benefits the local people. Over the last years I have met many very motivated and talented researchers, but all too often they do not have the resources to reach their full potential. Things that seem simple for those of us fortunate enough to be based in a first world country often are complicated for those who don’t. Whether it’s attending international conferences to stay up to date with what is new and network with other researchers, buying good quality equipment to do your research or writing scientific papers in a language that is very different to your own…

To me it seems logical to try and work with researchers and give something back for letting me do my work in their home country. Too often researchers or big international companies come in, do their thing (and in some cases make a huge profit out of it) without giving something back. “Bioprospecting“, the search for natural products or compounds to use and commercialise is becoming more common and is an important source of new medicines (among others). However, sometimes this turns into biopiracy, when compounds are taken without permission or without compensation. Which is why there is such a thing as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the newly ratified Nagoya Protocol. It is also one of the main reasons why the process of obtaining research permits in Indonesia is rather…complicated.

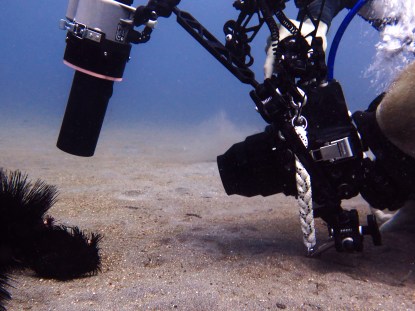

So I talked about my research and why I think it is important and very exciting. I also talked about some of the new things I found out (hopefully more about that in the near future) and about some of the ideas I have for new areas of research. Hopefully this was the start of more future collaborations with researchers and students in Hasanuddin. The little critters I’m studying can definitely do with some more research attention!

I’d also like to use this blog to say a big thank you to the people at Unhas who invited me (ibu Rohani and pak Jamaluddin) and to the people who showed up for my little talk. It was a great experience for me and I hope it won’t be the last time I visit.