I may not have been blogging much recently, but a lot has happened in the last few months. First and foremost, I completed and handed in my PhD-thesis. Since then I have been teaching, writing grant and job applications, and I’ve had a nice long holiday relaxing and traveling in Europe and diving in Indonesia.

In all honesty, handing in my PhD-thesis isn’t really news anymore since it’s been almost four months ago. That does not change anything about how happy and relieved I am that I managed to finish this epic project. Although this happiness might also have a slight tinge of regret as it means the end of more than 3 fantastic years of being absorbed by something that I love doing very much. By now I have also received the examiners’ comments back from my thesis, which were very positive, meaning that the whole process of finalising the PhD might be even quicker than I’d really like to.

Yours truly during my PhD-presentation, very happy days!

Why quicker than I’d like to? Mostly because it means I have to find a job now! I really, really like doing research, especially when it involves little critters or sandy ocean floors. So I will try my very best to keep on doing research on this, but post-PhD research jobs (so called “post-docs”) are hard to come by. Even harder when you study sand and animals that look like sand 😉 So I have been applying for positions all over the world, ranging from Australia, to Germany, the UK, Indonesia, etc.

This is all very exciting, since I might literally end up anywhere in the world. But as you can imagine, it also means a fair amount of insecurity of what life will look like in a few months time. The excitement about new projects and adventure always wins over the worries though 😀

But, just in case you’d happen to know someone who is looking for a researcher who knows his way around Southeast Asia, soft sediment, and cryptobenthic fauna, do give me a ring 😉

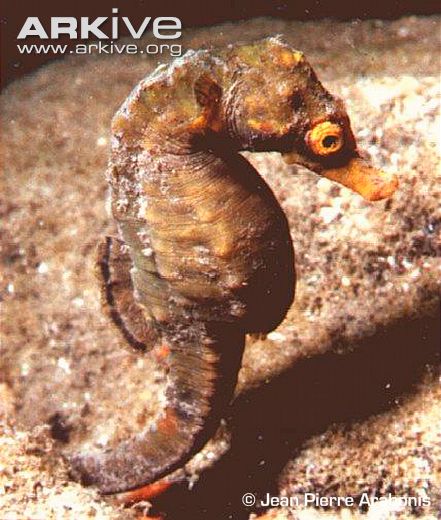

There are more exciting thing going on than just job-hunting! As a matter of fact, August will be a pretty busy, action-packed month. At the moment I am in Perth airport, almost ready to fly to South Africa. As you may or may not remember, a few months ago we (my friend Louw and me) received a grant from the Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund to conduct research on the endangered Knysna Seahorse (Hippocampus capensis). We have been working behind the scenes and preparing since, but now it is finally time to do the fieldwork portion of the work!

The species we’ll be studying: the Knysna seahorse (Hippocampus capensis)

To try and give everyone who is interested an idea of what marine science fieldwork is like, I am planning to blog frequently during the next 2 weeks. No promises about just of frequently, but I will do my very best to document trip and give you an insight of what it’s like (for me) to do the data collecting that is behind most of the stories I share here.

If you do not want to miss anything, you can always follow the blog (there’s a button on the site somewhere), you don’t need an account, you can just get the updates via email. Alternatively, I’ll try to post (almost) daily pictures on Instagram (crittersresearch) and Twitter (@DeBrauwerM) as well if you can’t be bothered reading and just want to see what it all looks like.

Finally, throughout this study, I very frequently observed divers touching marine life. Despite the fact that

Finally, throughout this study, I very frequently observed divers touching marine life. Despite the fact that