I have been doing quite a lot of night dives recently. Those who know me from when I was still working as a dive instructor might be a bit surprised by this, as I never use to be the biggest night dive enthusiast around. There are two reasons I’m swimming around in the dark a lot recently:

- Night diving in Lembeh Strait (and Indonesia in general) is pretty amazing

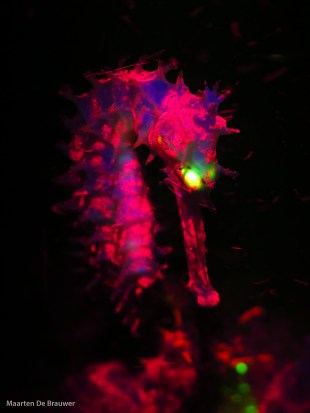

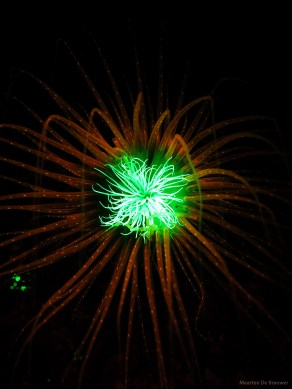

- I’ve been playing with a new toy that makes it all a bit more interesting: a high intensity blue light torch. This torch, combined with a yellow filter allows a diver to see “biofluorescence”

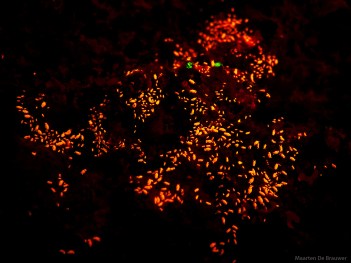

So as an excuse to post some very psychedelic photos, let me tell you a bit more about biofluorescence under water.

It is important to realise that biofluorescence is NOT the same as bioluminescence. The former needs an external light source (the sun, a dive torch,…), the latter means that the animal itself produces light. For more info on the differences, check out the site of the Luminescent labs.

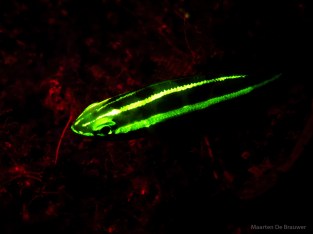

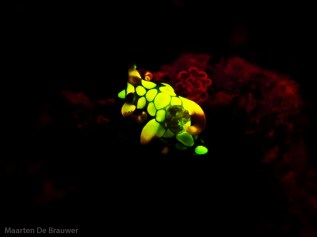

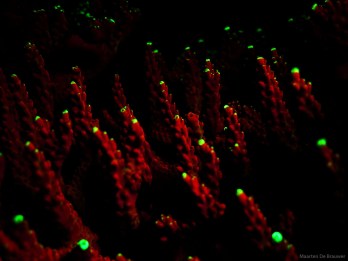

Biofluorescence under water has been described as early as 30 years ago and was first noted in corals and anemones. It has been used for years in coral research that looks at coral growth, diseases and bleaching. More recently however, people have started noticing that many more animals than just coral are fluorescent. A paper in 2008 described how many goby species show red fluorescence. Other publications have described fluorescence in many invertebrates such as mantis shrimps, crabs, worms, nudibranchs,… But I really got interested last year when a paper was published that described how fluorescence in fish was much more widespread than previously assumed. The reason it caught my attention is because it seems to be particularly common in “cryptically patterned species”, many of which happen to be the camouflaged little critters I’m so interested in.

So I got myself the necessary equipment and now I am trying to figure out what exactly fluoresces here in Lembeh, and maybe even getting a clue about why they fluoresce as well. There are a few theories out there: it could be used as a form of communication, it might be some sort of camouflage, it could even just be pure coincidence and we might be looking at a cool, but irrelevant quirky thing that evolved but serves no real purpose (I highly doubt this). Fish see the world differently than we do and many species can actually observe UV-light and fluorescence, which would lead me (and other researchers) to believe there is some function there. To prove these functions however, a lot more research and experiments are needed.

What matters most for this blog post, is that it looks rather amazing and that it shows a different, little known side of the underwater world. In case you were wondering, or doubting what you are seeing, none of the pictures in this post have been photoshopped beyond cropping and cleaning up some backscatter.

If you want to know more about how fluorescence works and how to take fluoro pictures yourself, this site is a good place to get started.