The research project I am working on might be one I designed and that will (hopefully) result in me getting a PhD degree, but I could never succeed in this without the help of many other people. I have got three supervisors in Australia, local counterparts here in Indonesia, connections in the dive world, friends and family who provide moral support,… And then there’s my trusty science hobbit, Luke. As much as everyone else has supported me and helped out so far, I could not have achieved a fraction of what I have in Indonesia without Luke’s help. So I am using this blog to thank him and to tell his story (and to shamelessly promote his awesome photography work while I’m at it).

Luke and I met in 2011 where we were both working for Coral Cay Conservation in Napantao, Philippines. He was one of the two science officers, while I was responsible for making sure everyone was diving safely. Luke and Jen (the other science officer) were amicable kown as science hobbits, a title that I have kept on using ever since. We shared a room for months, so we got to know each other very well. Besides sharing a passion for nudibranchs and by extension any other ocean critter, it turned out we also make great dive buddies.

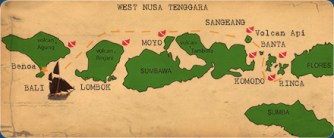

As most divers will know, diving with some buddies just works better than with others. It’s more than just safety and doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with how well you get along on land. I have dived with partners and friends who were great divers, but which just didn’t work as a buddy. Vice versa I’ve dived with people that I hardly knew on land, but with whom diving just went super smooth. Anyone who has ever had the chance (or bad luck) to dive with Luke and me will contest to the fact that we work well underwater. We not only know each other’s dive style, air consumption and intentions, we actually manage to have proper conversations while we’re diving. I have vivid (and hilarious) memories of us discussing which species of nudibranch we found on a dive in Komodo, ignoring the ripping currents because we needed to settle that particular point right then and there 😀

So who is this science hobbit really? I can tell you that he is not only a great diver, he is also one of the most knowledgeable field marine biologists I have ever met. You need coral identified? Ask Luke. Not sure what fish it is? Ask Luke. Need to know more about coral nurseries? Ask Luke. Want to build a coral reef aquarium, do fish surveys, know more about conservation, diving in Fiji, Madagascar or Philippines? Luke’s your man! I even have to admit that he might be better at spotting baby frogfish than I am. On top of all that, he is also genuinely a nice guy who is great fun to work with. All of this is probably why he has been asked to work with so many NGOs and researchers in places like Fiji, Philippines, Maldives, Madagascar, Ecuador, Indonesia,… It is definitely the reason why I asked him to come and help me in Indonesia for the past 3 months.

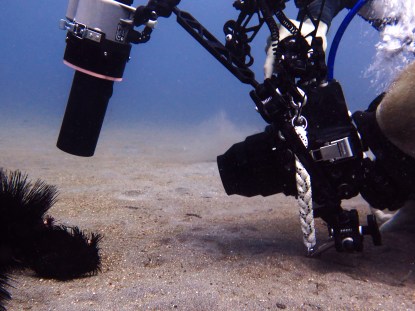

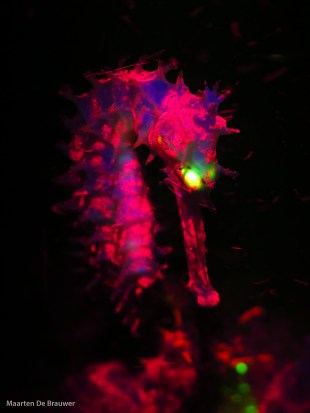

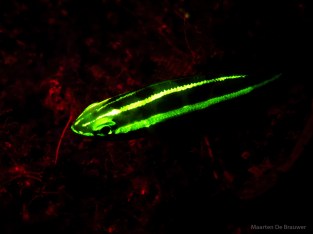

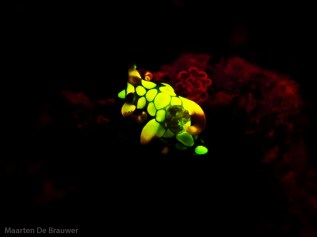

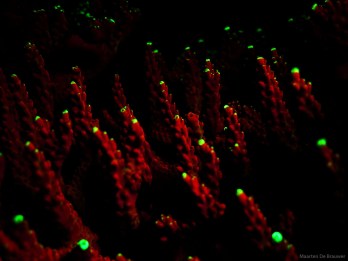

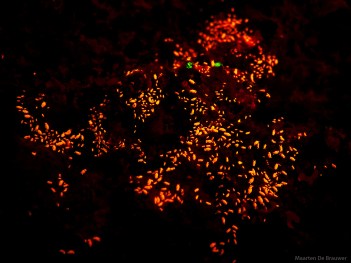

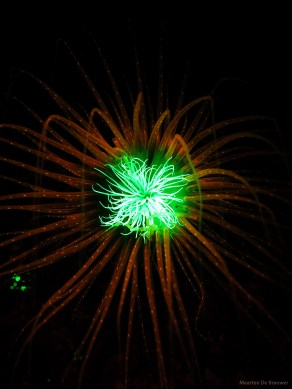

To add to those skills, he is also not half bad as a photographer. When I say not half bad, I mean pretty bloody amazing! Most of the pictures on this blog are his work, so go back, read through some of the posts and have a look at the pictures. Even better, check out his website or facebook page. You can even order prints of his pictures as well, so check it out! On the site you can order prints of some of his best shots. At the moment Luke is giving 50% off prints for the first 20 prints ordered, just use the code FROGFISH when ordering your prints. If anyone is still looking for Christmas or birthday present ideas for ocean lovers, it’s your chance to get a good deal.

Unfortunately I had to say goodbye to one of my best friends and greatest colleagues ever. He has been whisked away to Australia by his girlfriend to go and explore that part of the world. In all fairness to Katie, she did let me use him for a good 3 months, significantly postponing their Australia plans. Besides that, she is just as amazing a person as Luke is, so I am wishing both of them all the best on their new adventures. I sincerely hope they have the best of times together and that they get all the good luck they both deserve.

Once again a massive thank you Mr. Luke, hoping our next dive together will be sooner rather than later!