The last two months I have been running an experiment that involves keeping more than 30 seahorses in aquaria. Not because I am trying to become a marine aquarium expert or because I like seeing fish in tanks. On a personal level I think there are too many environmental issues with aquarium trade to get into it myself. Overfishing of species like Banggai Cardinalfish and Mandarinfish are two examples that come to mind. But this post is not about the aquarium trade, so I will leave those particular issues for another time. While I prefer seeing seahorses in the ocean, for this experiment it was necessary to bring them to the “Curtin Aquatic Research Laboratories” (CARL). This blog explains some of the challenges that come with keeping seahorses healthy in an aquarium. If you are considering ever keeping seahorses yourself, please read this blog carefully.

West Australian Seahorses (Hippocampus subelongatus) in their artificial seagrass home

DISCLAIMER: This blog describes scientific research, catching seahorses as a private person is NOT allowed in Australia. If you have any questions about keeping seahorses, feel free to contact me in the comments section.

First challenge: Permits. It takes a lots of paperwork to be allowed to do research on seahorses in captivity. Seahorses are on Appendix II of CITES (Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species), which means they cannot be traded internationally if they are smaller than 10cm. But it does not mean that seahorses cannot be fished. As a matter of fact, they are caught in their millions for traditional Chinese medicine! For this experiment it was crucial to use wild-caught West Australian seahorses (Hippocampus subelongatus), which meant applying for permits from the Department of Fisheries and seeking approval from the Department of Parks And Wildlife. Besides government paperwork, doing any kind of research with animals means writing up extensive application (close to 40 pages) for the universities’ ethics committee to ensure proper treatment of the animals while in my care.

Seahorse tag with red elastomer so it can be identified later

Second challenge: Catching seahorses. As anyone who has ever looked for seahorses can attest to, they are hard to find. There are a few sites around Perth where there are plenty of seahorses to be found, but getting all seahorses from one location would have a huge impact on that particular site. To limit the impact of my collecting, I spread out my fish-catching over multiple sites. To further reduce impact, I did not take any pregnant males or any seahorses that were clearly couples ready to mate. Since I needed a variety of sizes and a similar amount of males and females, collecting enough seahorses took a lot of dives spread out over a few weeks. Once seahorses were caught, they also needed to be transported safely to our facility, which meant not going too far, and using specialised tools to (sturdy catch bags, coolers, oxygen, etc.) to reduce stress for the animals during transport.

Third challenge: High quality aquaria. Seahorses are notoriously difficult to keep in tanks. They are very sensitive to bad water quality, which can lead to all kinds of issues. Preparing the aquaria started 6 weeks ahead of catching the seahorses. This is done to ensure that the biofilters that ensure good water quality get properly established. The tanks themselves need to be large and high enough to house seahorses, and they need hold-fasts that mimic seagrass so the seahorses have something to cling on to.

First arrivals in the tanks

Seahorses live in salt water, so getting seawater is another issue. Our labs are not directly by the ocean, so we need to import seawater. This then gets sterilised (using UV filters) before we use it. Water quality needs to be monitored daily and adjustments made where needed. This means no weekends off since minor problems could mean dead seahorses. While we have the aquaria and equipment available at CARL, the costs of this would be considerable for a private person.

Fourth challenge: Food. This is probably the biggest challenge of them all. Wild-caught seahorses only eat live food and will not eat dry or frozen fish food. So we need small shrimp to feed them. In our case we are using artemia (= sea monkeys = brine shrimp). Artemia are tiny (less than 1mm) when they hatch, but our seahorses will only eat them when they are about 1cm in size, which means they have to be grown out for a few weeks before feeding. So we prepared 3 different artemia cultures, each one set up 2 weeks apart to ensure a constant supply of right-sized food. The artemia also need to be fed, in their case with algae. This means 5 cultures of different species of algae to make sure our seahorse-food stayed healthy and fat. Both algae and artemia water quality also need to be monitored, since dead algae/artemia would ultimately mean starving seahorses. To top it off, artemia are not naturally nutritious enough to be the only food source for seahorses. So we added an artemia enrichment-tank (where we add a fatty mix of all nutrients needed for healthy seahorses), which needs to be set up, cleaned, and harvested every day. The result is that for 3 tanks with seahorses, we have 9 tanks for their food preparation. I’m not sure if you have enough space for that at home?

Fifth challenge: Feeding. As if breeding the food was not hard enough already, feeding them makes it even more complicated. Seahorses have no real stomach to speak of, so they are lousy at digesting their food properly. Because of this they need to eat almost constantly, which is possible in the wild, but harder in an aquarium where too much food will lead to bad water quality. In our case it means feeding them three times per day, every day (bye bye weekends or late nights!). Since our guys have been caught so recently, we can’t just drop the food in the tank and leave it. What works best is hand feeding them with a pipette to make sure they see the food and eat it. Each feeding session takes about 30 minutes, with longer sessions (90 minutes) in the morning, since food has to be harvested first and then a new culture prepared for the next day.

Feeding the seahorses using a pippette

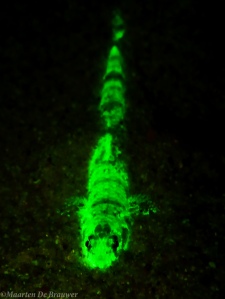

Sixth challenge: Keeping them healthy. Seahorses kept in aquaria are prone to infections, so besides good water quality it is important to keep everything clean. This means sterilizing all the equipment we use, only handling seahorses with surgical gloves on, keeping workspaces clean, etc. Regardless of this, infections can still happen. So far I have had to treat one infection with freshwater baths. Earlier this week two males had bubbles in their pouch (common in tank-kept seahorses), which needed to be removed using syringes and gentle pouch-massaging. You read that correctly, my PhD involves giving belly-rubs to seahorses.

All of this is needed just to keep our seahorses alive. I won’t go into what it means to actually run the experiments as well. But if you managed to read this entire post, it should be clear that keeping seahorses means a LOT of work. I am only able to do this because I can use the great facilities at Curtin University and because I have the support of experienced lab technicians, dedicated volunteers, and supervisors with experience in aquaculture. After 2 months of caring for my seahorses, I feel even more strongly than before that seahorses should be in the ocean and not in a small aquarium. If you do want to keep them yourself, think it through before you begin. Make sure you have the right setup BEFORE buying seahorses, only buy captive bred animals and be prepared to sacrifice a lot of your free time for your seahorses.

To finish, here is a short video of one of our seahorses eating artemia: