Now that my PhD thesis has been submitted, it is time to start blogging again! In the very near future I will write a new blog about this whole PhD-writing experience, but for now I will tell you about a new paper that has been published recently in the scientific journal Ocean and Coastal Management.

The paper, “Known unknowns: Conservation and research priorities for soft sediment fauna that supports a valuable scuba diving industry“, describes which species are most important to muck dive tourism, and how much research and conservation work has been done on them. I investigated this using a specific method that is pretty new and has not been used in conservation work until now.

Who doesn’t like a frogfish (Antennarius pictus)?

Since these the method and the results will be of interest to different people, this blog is split in two parts:

- How did I do the research?

- What are the results?

If you are a scuba diver, a dive professional, a travel agent or otherwise mostly interested in the cute animals, it’s completely fine to head straight to number two (even though you will be missing out). If you are a resource manager, work for an NGO, are interested in marketing, or conduct research on flagship species, definitely read the first part of this blog as well!

First section: the Best – Worst Scaling method and why everyone should start using it

It is important to first think about why anyone would care about which species are important to muck dive tourism, or any kind of tourism by extension. The obvious answer would be “marketing”, if you know which species attract the tourists, you can use them in your advertising and that way attract more tourists. If that is too capitalistic for you, remember that dive tourism provides (mostly) sustainable incomes to thousands of people around the world. But there is more, people might not visit a destination, but still care very deeply about certain species. This principle has been used (very successfully) by many conservation organisations to set up fundraising campaigns. The best known example is probably the World Wildlife Fund, which uses the panda bear as a logo, even if they are trying to protect many more species.

It is important to first think about why anyone would care about which species are important to muck dive tourism, or any kind of tourism by extension. The obvious answer would be “marketing”, if you know which species attract the tourists, you can use them in your advertising and that way attract more tourists. If that is too capitalistic for you, remember that dive tourism provides (mostly) sustainable incomes to thousands of people around the world. But there is more, people might not visit a destination, but still care very deeply about certain species. This principle has been used (very successfully) by many conservation organisations to set up fundraising campaigns. The best known example is probably the World Wildlife Fund, which uses the panda bear as a logo, even if they are trying to protect many more species.

Blue ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena sp.) are popular with divers, maybe because of the cuteness combined with its deadly bite?

With that in mind, how do you find out which are the animals that people care about? You can obviously just ask people what they like, get them to make a list of top 5 animals, rank a number of animals in preferred order, give scores to certain animals, etc. But there are some serious problems with most of these methods such as:

- They are not always reliable, since some people will be consistently more or less positive, or have cultural biases, throwing off your scaling

- They can be very labour-intensive (=expensive) to properly design and collect data on

- Statistical analyses of the results are usually very hard to get right

- It is very difficult to say how the preferences vary between different groups of people (male-female, age, nationality, etc.)

To overcome these issues, we used the “Best-Worst scaling method” and compared it to a traditional survey. This method has been around for a few years, but is mostly used in food marketing (wine!) and patient care in medical research. The big benefit of Best-Worst scaling is that doing the stats is really easy, and without too much extra effort you can also easily interpret how different groups have different preferences.

Flamboyant cuttlefish (Metasepia pfefferi) might not be popular with researchers, but divers love them!

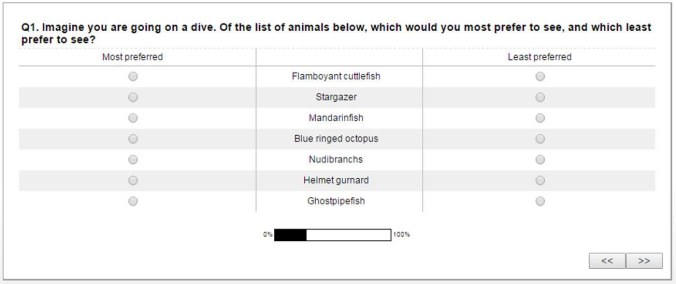

Without going into too much detail, the basic design of Best-Worst scaling is that you ask people what they would like MOST and LEAST from a fixed set of animals (or any other thing you are investigating). There are plenty of online platforms (we used Qualtrics) that allow you to design this kind of question, so it’s quick, easy and cheap. Getting results is as simple as subtracting the amount of times an animal was picked as most preferred and the number of times it was least preferred.

Example of a Best-Worst Scaling question

The reason I am describing this method here, is that it is just not known enough in the conservation, or even tourism world. It has the potential to allow all kinds of organisations with limited funding (NGOs, marine parks, or even dive centers) to investigate why people would visit / where they will go / what they care about. Which, eventually, might lead to more research and conservation on those species.

Second section: Which species drive muck dive tourism?

The mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus), number 1 on many muck divers’ wish list

The results of the surveys won’t come as a shock for avid muck divers or people in dive tourism, but do seem to surprise from people unfamiliar with muck diving. Here is the top 10:

- Mimic octopus / wunderpus

- Blue ringed octopus

- Rhinopias

- Flamboyant cuttlefish

- Frogfish

- Pygmy seahorses

- Other octopus species (e.g. Mototi octopus)

- Rare crabs (e.g. Boxer crabs)

- Harlequin shrimp

- Nudibranchs

While other species such as seahorses or ghostpipefishes are also important to muck divers, a dive location that does not offer the potential to see at least a few of the top 10 species is unlikely to attract many divers.

Nudibranchs (Tambja sp.) are always popular with photographers

Some differences did occur between diver groups of divers. Older and experienced divers seemed more interested in rare shrimp than other groups. The preferences of starting divers was poorly defined, but their dislikes were most pronounced than experienced divers. Photographers in particular are interested in species like the mimic octopus, potentially because of their interesting behaviour, although that would have to be investigated in a follow-up study.

The final step of our study was to look at how much we know about the animals most important for muck dive tourism. The answer is simple: not much. For most species researchers have not yet investigated if they are threatened, or not enough is known about them to assess their risk of extinction. It does not look like this will chance soon either. The combined amount of research conducted on the top 10 species in the last 20 years is less than 15% of the numbers of papers published on bottlenose dolphins (1 species) in the same time. Which are not threatened by extinction in case you were wondering. To give you another comparison, from 1997 until now, 2 papers have been published on the flamboyant cuttlefish, compared to more than 3000 on bottlenose dolphins.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not saying we should stop researching dolphins, but perhaps it is time that some of the research effort and conservation money is also invested in the critters that make muck divers tick?

Harlequin shrimp (Hymenocera elegans), popular with divers AND the aquarium trade