Algae or a pipefish pretending to be algae?

At some point or other, all of us have pretended to be something that we are not. From trying to look old enough to buy alcohol as a teenager, to keeping your head low and pretending to be a pot plant in the corner of the office when the boss is looking for someone to take notes during a meeting. Some people might pretend more often than others, people might have good reasons for wanting to look like someone (or something) they are not, and some individuals might have less than innocent intentions when hiding their true identity. The same thing happens in the oceans but the stakes are usually higher than (trying to) look cool with a beer, or the tedium of having to take notes. A critter’s skill at pretending often means the difference between getting dinner or being dinner…

The ocean-pretending I am talking about is more commonly known as camouflage and mimicry. The terms are frequently mixed up or even assumed to be synonyms, but they are two different concepts. To distinguish between the two, it helps to know that the goals of camouflage and mimicry are opposite from each other. Animals using camouflage are trying very hard not to be seen, like you trying to be a pot plant instead of a potential scribe. Mimicry attempts to do the opposite: wanting to be seen, while hoping observers will believe you are someone else, like our teenager bluffing he’s old enough to drink.

Usually when biologists (who know their shit) talk about camouflage, they are thinking of mobile animals that are pretending to be objects or animals that don’t move; these objects could be plants, rocks, sand, sponges, etc. When those same biologists talk about mimicry, they mean active animals that pretend to be different species of active animals. But that is just the start of it, the obvious question is why? What are the reasons behind camouflage and mimicry? As a rule, fish don’t like alcohol, so there must be some other cunning plan.

For camouflage it boils down to two options: defensive or aggressive. People tend to intuitively understand defensive camouflage: hiding so you don’t get eaten or killed. Two ocean examples are seahorses pretending to be seafans or crustaceans looking like sponges. Aggressive camouflage is when an animal tries not to be seen, so it can eat unsuspecting animals coming closer. Frogfish are masters at this, so are most scorpionfish, and many other species. It is perfectly possible for an animal to use both defensive and aggressive camouflage at the same time. Think about the human version: soldiers wearing camouflage do not want to get shot, while aiming their guns at the enemy.

Mimicry has similar uses, depending on what the animal mimics. Unlike camouflage, mimicry needs a distinctive “model species”, which is imitated by the “mimic”. Depending on the nature of the model and the mimic, we distinguish three kinds of mimicry. Batesian mimicry has a dangerous model, but a harmless mimic. Mullerian mimicry has a dangerous model and a dangerous mimic. The last type, Peckhamian mimicry, has a harmless model, but a dangerous mimic.

Batesian mimicry can be compared with our teenager trying to buy alcohol. He might try to look like the real deal, but really is not. A great ocean example is the (non-toxic) baby pinnate batfish (Platax pinnatus), which look like a toxic flatworm. Or baby sea cucumbers pretending to be toxic nudibranchs. Predators assume the mimic is toxic, so they avoid eating it, good news for the mimic!

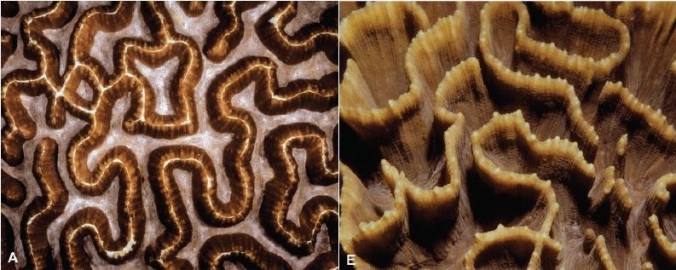

In Mullerian mimicry both mimic and model are “the real deal”. This is very common in nudibranchs of the Phyllidiidae family. Most species in this family are very toxic and they all look very much alike. When a predator tries to eat one species, he’ll learn to avoid the other similar looking species as well. A bit like the leather-clad members of different motorbike gangs which look equally dangerous to outsiders. The bikers can tell the difference between other gangs, but I would advise against picking a fight with any of them.

Peckhamian or aggressive mimicry happens when the mimic pretends to be a harmless model, usually to get close to prey. This method is used by predators like dottybacks, who pretend to be harmless damselfish so they can get close enough to juvenile damselfish to eat them. A (purely hypothetical) human example could be a person living in a fancy white house, who pretends to be a silly orange clown, but in reality is a dangerous would-be dictator. As it turns out, land is no different than the ocean: the animals that believe in the illusion are most likely to suffer from it.

Aggressive camouflage in action: this dragonet failed to see the lizardfish hiding in the sand.