This is the second guestblog by Daniel Geary, resident marine biologist and frogfish-enthusiast at Atmosphere Resort in Dauin, Philippines. You can read his first blog here. In this new guestblog Daniel explores the history of frogfish research and provides an introduction to a few common and not-so-common frogfish species.

This is the second guestblog by Daniel Geary, resident marine biologist and frogfish-enthusiast at Atmosphere Resort in Dauin, Philippines. You can read his first blog here. In this new guestblog Daniel explores the history of frogfish research and provides an introduction to a few common and not-so-common frogfish species.

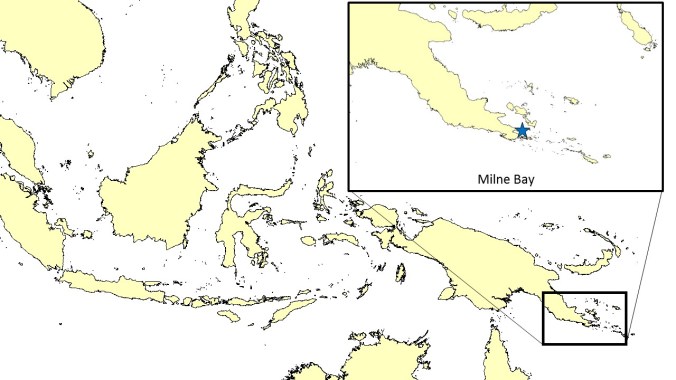

There are many places across the globe where divers can see frogfish, but the Philippines (especially the Dauin area) is one of the best frogfish destinations of them all. I have personally seen thirteen species in this country, including 11 species here in Dauin. Sometimes we will see over 30 individuals on a single dive! It is not uncommon for some of the frogfish to stay on the same site for over a year, especially Giant Frogfish. Another great destination for frogfish is Indonesia, especially Lembeh, Ambon, and also some places in Komodo. Generally, if there is good muck diving, there is good potential for frogfish action. Australia also has some unique frogfish species, as well as the Caribbean, where there are a few places with reliable frogfish sightings.

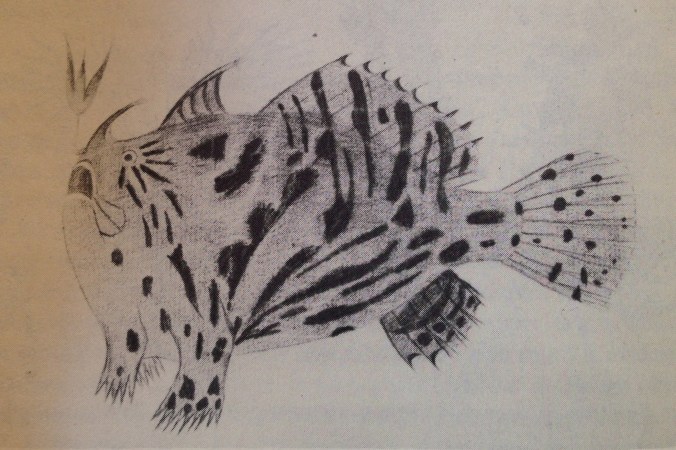

Although frogfish are relatively well known critters to divers in the Indo-Pacific, this has not always been the case. Stories of frogfish and their accompanying drawings and sketches have existed for hundreds of years, with encounters spanning the globe. The first ever documented frogfish comes from Brazil. At some point before 1630, a drawing was given to the director of the Dutch West India Company. A woodcut was made from this drawing, and that woodcut was published in 1633. The first color drawing appeared in 1719, published by Louis Renard, an agent to King George I of England. He published a collection of color drawings of Indo-Pacific fish and other organisms and some of these represent the earliest published figures of Indo-Pacific frogfish. One was called Sambia or Loop-visch which translates directly to “walking fish.”

First colour drawing of a frogfish – Louis Renard 1719

Albertus Seba and Philibert Commerson were two important scientists in the 1700s when it comes to frogfish. Seba believed frogfish were amphibians and tried very hard -incorrectly of course – to prove that they were the link between tadpoles and frogs, although anyone who has seen a baby frogfish knows this to be false. Even though he incorrectly identified a few nudibranchs as juvenile frogfish, he was still able to identify two species, the Hairy Frogfish (Antennarius striatus) and the Sargassumfish (Histrio histrio) during his studies. Commerson was the first scientist to focus solely on frogfish. He was a botanist and naturalist employed by the King of France and he described three species from Mauritius (Painted Frogfish – Antennarius pictus, Giant frogfish – Antennarius commerson, Hairy Frogfish – Antennarius striatus).

Commerson’s drawing of the hairy frogfish – Antennarius striatus

There have been plenty of identification problems when it comes to frogfish, even today. Frogfish colorations and patterns are highly variable, so it is nice to know people have been struggling with frogfish identification for hundreds of years. Albert Gunther, a scientist who attempted describe the different species of frogfish, said in 1861 that “[their] variability is so great, that scarcely two specimens will be found which are exactly alike…although I have not the slightest doubt that more than one-half of [the species] will prove to be individual varieties”. He listed over 30 species, but only 9 of those species are still accepted today. Since 1758 there have been over 165 species described and over 350 combinations of names. Currently there are around 50 accepted species, roughly one third of the total species described.

FROGFISH SPECIES PROFILES

Painted Frogfish – Antennarius pictus

This is the most abundant frogfish species in the Indo-Pacific. They can be identified by having 3 distinctive spots on their tail. They prefer to live near sponges, rocks, ropes, mooring blocks, and car tires. They can grow to a maximum size of around 15 cm.

Painted frogfish (Antennarius pictus) with its typical three tail spots

Sargassumfish – Histrio histrio

This is the species with the largest distribution. They can be found in floating seaweed or debris as well as anchored seaweed and other marine plants. They can reach a maximum size of around 15 cm and are often sold in the marine aquarium trade.

Sargassumfish (Histrio histrio), a surprisingly good swimmer that lives on floating seaweed

Psychedelic Frogfish – Histiophryne psychedelica

This is one of the rarest frogfish species. They are only found in Ambon, Indonesia at a handful of dive sites, usually at around 2-3m hidden in rock crevices or in coral rubble.

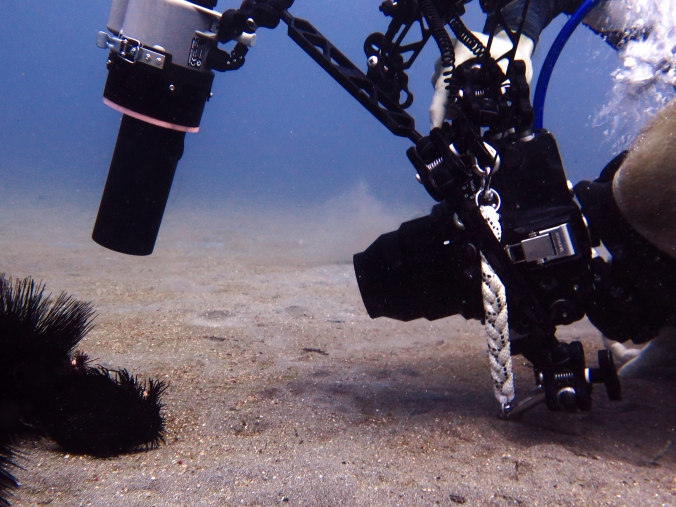

“Snooted” picture of a psychedelic frogfish (Histiophryne psychedelica)

Giant Frogfish – Antennarius commerson

This is the biggest frogfish species, reaching lengths of more than 40 cm. They prefer to live on sponges and have two large spots on their tail, as well as lines coming from the eye and enlarged dorsal spines.

Giant frogfish (Antennarius commerson) resting on a sponge. Note the two tail spots

Ocellated Frogfish – Nudiantennarius subteres

This frogfish species is the “newest” frogfish species. Originally thought to be a new species, it turns out this species is the previously described, relatively unknown “Deepwater Frogfish”, although the lure is incorrect in the original drawing. It was thought that the adults lived deep and only the juveniles were found in the shallows, but adult mating pairs of this species have been seen at less than 10m depth. They grow to around 5 cm.

Typical coloration of the Ocellated frogfish (Nudiantennarius subteres)