It turns out that moving halfway across the world and diving into a new job is more time consuming than I expected, so I haven’t been keeping up with the blog recently. I’m slowly starting to get more organised and in the coming weeks I will try to catch up with summaries of papers that I’ve published recently.

The paper “High diversity, but low abundance of cryptobenthic fishes on soft sediment habitats in Southeast Asia” was published almost a year ago in the journal Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. It was one of the key papers of my PhD and describes the diversity of critters on sandy habitats in Indonesia and the Philippines.

If you have ever been muck diving it won’t come as a surprise to you that there is some very exciting marine life to be found on sandy bottoms. When you mention places like Lembeh Strait, Anilao, or Dauin to keen divers – especially photographers – they either get lyrical about the amazing pictures they took there, or will tell you about their plans for visiting any of the above places to go see some crazy marine life.

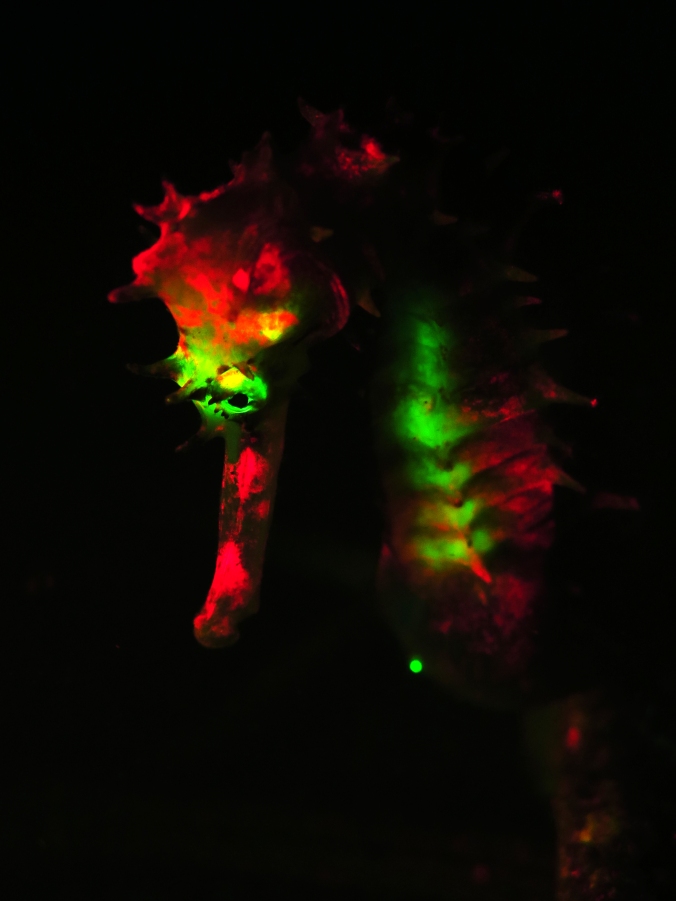

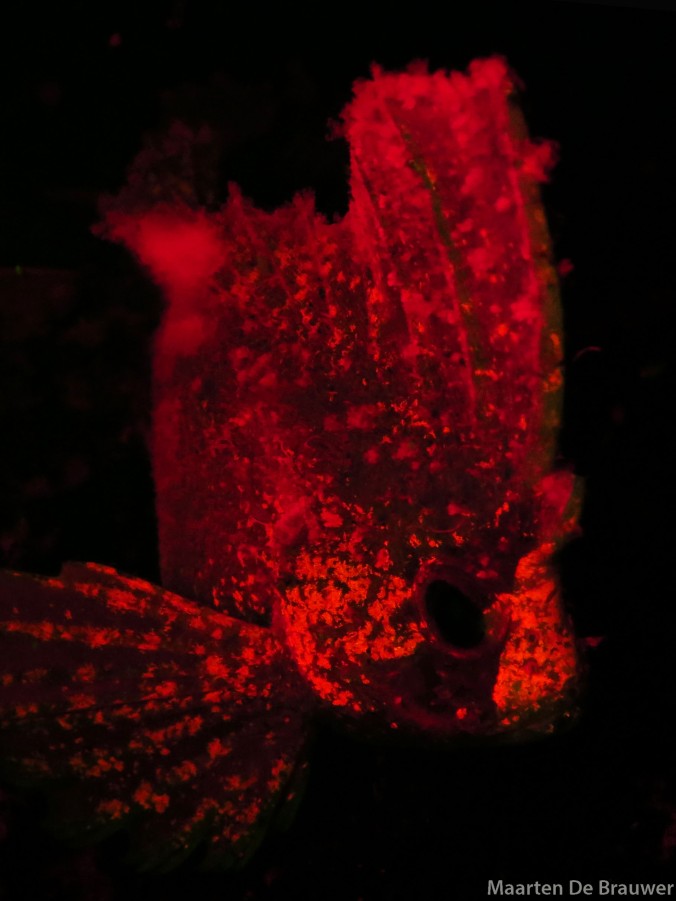

Species like this painted frogfish (Antennarius pictus) are popular with muck divers

In fact, the popularity of these sandy critters is so great, that the divers visiting Southeast Asia for muck diving bring in more than $150 million of revenue each year, supporting thousands of sustainable jobs! With so much money and jobs involved, it would be normal to expect researchers and conservationists to be interested in knowing which animals live on tropical sandy slopes. Unfortunately, that assumption would be wrong, surprisingly little is known about soft sediment (=sandy) habitats in the tropics. Even basic knowledge such as which animals live where is often unknown.

Luckily things are changing! Scientific interest in “cryptobenthic species” – the small, camouflaged critters this site is all about – is definitely increasing, with excellent work being doing on coral reefs by colleagues from across the world. We are starting to understand just how important they are for coral reefs and how very diverse cryptobenthic species can be.

What I am interested in though, is what is going on with the critters that live away from reefs. Are the critters living on the sand as diverse as those one coral reefs? Which species are most common? What causes species to live in one area, but not another? To answer these questions I set of with my good friend Luke for a 3 month dive survey trip that took us to Lembeh Strait, the north coast of Bali, and the sandy slopes of Dauin.

Surveying soft sediment critters in Dauin. Photo: Luke Gordon

During our survey dives, we not only counted and identified the fish we saw, we also measured a bunch of other factors that could have an effect on the presence of critters. We wanted to know whether depth, benthic cover (growth of algae, coral, sponges etc), or the characteristics of the sediment played a role in which species we found.

So what did we find?

One of the most interesting results is that the diversity (number of species) of cryptobenthic species was very high, higher in fact than the cryptobenthic fish diversity on many coral reefs! In contrast, the abundance (number of individuals) was much, much lower than what is found on coral reefs. To put it in perspective, if a normal coral reef would be an aquarium with 300 cryptobenthic fish of 15 different species crammed inside, soft sediment habitats would be the same aquarium with 30 fish of 16 species.

When looking at environmental factors, one of the most important factors that influenced where species lived, was the characteristics of the sediment. For small critters it makes a big difference whether the sand is powdery fine, or coarse like gravel. There seems to be a middle ground where the size of the sediment seems ideal for many critters. The tricky part is that the characteristics of sediment are in a large part determined by other processes such as currents or wave action. For now it is too early to conclude whether critters are found in these places because of the type of sediment or because of other factors that shape the sediment!

The amount of growth on the bottom played a role as well, particularly when algae or sponges were present, which makes sense as it offers variation in the habitat and potential hiding places for some species. Depth differences played a minor role in some regions (Daiun, Bali), but did not make a real difference in Lembeh. The limited effect of depth could partially be due to the fact that we did not survey deeper than 16m (university diving regulations are quite restrictive). It would be a great follow-up study to compare with deeper depths, as I am sure they will give very different results.

What does it all mean?

This study was (as far as I know) the first one ever to investigate the cryptobenthic fish in soft sediment habitats. The unexpectedly high diversity and very low abundance means there is a lot more species out there than what was assumed, but that we have to look much harder to find them. I mostly see our results as a starting point to guide further research. We have only uncovered a fraction of what is out there and are not even close to really understanding how tropical soft sediment systems function. While this provides an exciting opportunity for scientists like me to new research, it also means that we do not yet know how environmental threats such climate change or overfishing will impact species living on soft sediment. We do not know yet if the species that muck dive tourism depends on need protection, or how to best protect them if they do.

We might not know yet what the future holds for sand-specialists like this whiteface waspfish (Richardsonichthys leaucogaster), but I am hoping to find out!

So why does this animal deserve the effort of searching sandy plains for days on end, in the hope catching a glimpse of it? To start with (the name is a bit of a give-away) they are very flamboyant critters. We are talking yellows, pinks, blacks and whites, all at once! If that wasn’t enough, they often change their colours into “traveling waves”, even more so than normal cuttlefish or octopuses. From my experience, smaller Flamboyant Cuttlefishes have the brightest colours and make the most extravagant displays. When I write small, I do mean really small: adults do not grow much bigger than 8cm. They ideally sized Flamboyant Cuttlefish for the best colour-show would be around 3-5 cm!

So why does this animal deserve the effort of searching sandy plains for days on end, in the hope catching a glimpse of it? To start with (the name is a bit of a give-away) they are very flamboyant critters. We are talking yellows, pinks, blacks and whites, all at once! If that wasn’t enough, they often change their colours into “traveling waves”, even more so than normal cuttlefish or octopuses. From my experience, smaller Flamboyant Cuttlefishes have the brightest colours and make the most extravagant displays. When I write small, I do mean really small: adults do not grow much bigger than 8cm. They ideally sized Flamboyant Cuttlefish for the best colour-show would be around 3-5 cm!