The last 3 years of my life have been dedicated to intensely studying critters and socio-economics related to “muck diving”. While this is a relatively common term in the scuba diving world, the vast majority of people haven’t got a clue what muck diving is. I can’t count the number of times people at conferences, meetings, drinks, etc. have gone: “You study what diving???”. Marine scientists seem to prefer hearing “Cryptobenthic fish assemblages on tropical sublittoral soft sediment habitats” than “Critters in the muck”. Each to its own I guess?

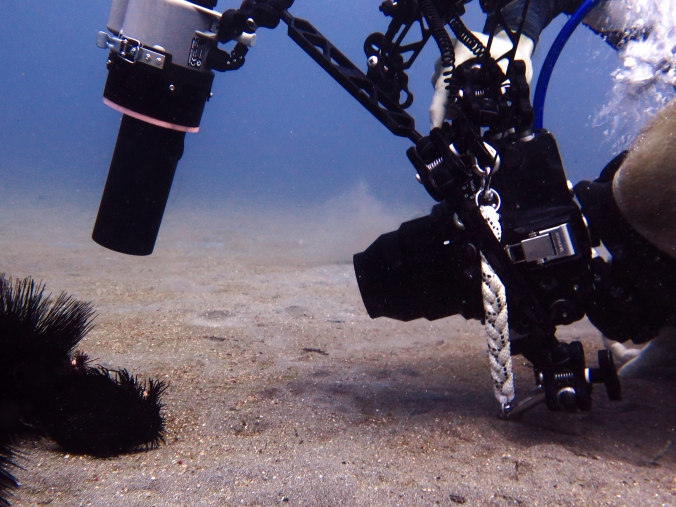

Classic muck diving scene (Photo: Dragos Dumitrescu)

It’s not just scientists who are confused, a lot of divers have questions about muck, or at the very least are curious about how it started and where the name came from, so I decided to dig a bit deeper and find out some interesting facts about the origins of muck diving. If you have never heard of muck diving or just aren’t sure what it is, here is how I defined it in my last paper:

“Scuba diving in soft sediment habitats with limited landscape features, with

the explicit goal to observe or photograph rare, unusual, or cryptic species that are seldom seen on coral reefs.”

Or easier: Diving on sand/mud/rubble to find cool animals you don’t see on normal divesites. The word “muck” means either “Dirt, rubbish, or waste matter” or even worse “Farmyard manure, widely used as fertilizer”. In British English it is also used for “Something regarded as distasteful, unpleasant, or of poor quality”. I would guess that it’s the combination of the first and last meanings that inspired the people who started this type of diving.

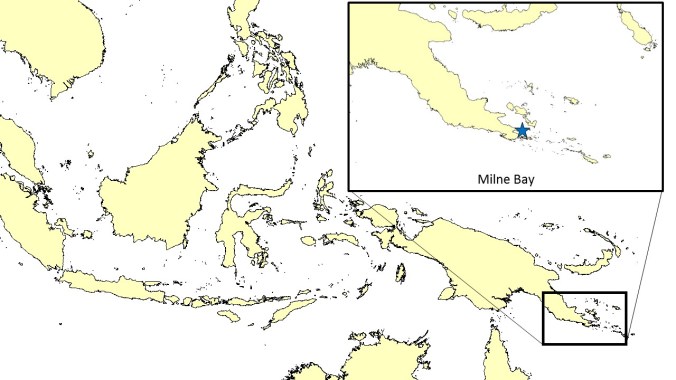

Muck diving in its current shape has its origins in Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. On a site called Dinah’s beach, where Bob Halstead decided to try to do a dive on the site where their boat (the MV Telita) was anchored. The divers were skeptical at first as the site was mostly sand and did not look very appealing, but after discovering tonnes of creatures they had never seen before they were sold and muck diving was born. From its origins in Papua New Guinea, muck diving caught on and became popular across the world, but no place is as well known for muck diving as Lembeh Strait in Indonesia.

Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea, where it all started

It is clear why Lembeh is famous with muck divers, as it really is a great place to dive and find some of the world’s most amazing critters. But how did muck diving in Lembeh kick off? What many people don’t know, is that Lembeh’s origin-story as the world’s most famous muck dive destination is pretty grim. The first resort in Lembeh (Kungkungan Bay Resort) was built in 1994, but the owners did not build their resort with critters in mind….

Back in those days, Lembeh was one of the best sites in the region to watch the big stuff. The plankton-rich waters of Lembeh Strait attracted scores of manta rays, dolphins, sharks,… Until 1996, when mankind showed just how destructive it could be. In March of that year, foreign fishermen came in and (illegally) installed the “Curtains of death”. These were huge nets, placed across the migratory routes of the large fish near Lembeh Strait. The nets were deadly efficient, during the 11 months they were used they caught:

- 1424 manta rays

- 577 pilot whales

- 18 whales

- 257 dolphins

- 326 sharks (including whale sharks)

- 84 turtles

- many other animals including turtles and marlins

The original article about the curtains of death can’t be found online, but if you are interested, send me an email and I can send a copy. If you want to know more about destructive fishing in Indonesia, this is an interesting source start with.

Peaceful Lembeh Strait has a turbulent history

The numbers are staggering, and for the few tourism operators in the area it must have been quite a shock. Until they discovered that Lembeh had much more to offer than just the big stuff. While there are no records of it, the story goes that muck diving in the area only properly got started when people started looking down at the sand instead of up at the manta rays. It makes me wonder what the area would have looked liked otherwise, and if muck diving would exist in the way it does now…

As it is now, muck diving is big, it attracts divers from across the globe and new critter hot spots keep on being discovered far beyond from where it all started. It’s exciting to think about how much more we will discover in the future! For me, one of the changes I would like to see, is the actual term “muck diving”. The name coined by Bob Halstead stuck, but I think most people in the diving (and academic) world agree that it isn’t really the most inviting name. I’d like to hear your suggestions (below in comments) on more suitable names for this type of diving and the divers doing it. If I get enough suggestions, I’ll organise a poll later to see what is preferred by divers around the world!

It’s all about finding the small stuff – baby Painted frogfish (Antennarius pictus)

PS: Originally I wanted the full title of this blog to be “On the origin of muck diving by Means of Photographer Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured divesites in the search for Critters”. But the long title might have put off those readers who didn’t immediately get the very nerdy biology pun.