This week I attended the CommOcean 2016 conference in Belgium. CommOcean was all about marine science communication and what the best ways are for marine scientists to interact with the general public. Science communication is about more than just reaching non-scientists, but also about making an impact and transforming how people perceive the ocean, it’s about making a positive change. But why would anyone really care about the ocean, or even more, change their day-to-day behaviour for it? A question particularly relevant if you live far away from the sea or don’t have a taste for fish.

The CommOcean2016 crowd in front of the beautiful conference venue in Bruges

The thing is, the ocean matters big time, for everyone, everywhere. On a global scale, the ocean produces more than 50% of the oxygen we breathe (more than trees!). If breathing isn’t your thing, the ocean also provides other trivial things such as food, cures to certain cancers and other diseases, a way to transport most goods around the globe (90% of international trade), and so much more. Current human impacts such as climate change can and will have effects on everyone, even those living furthest away from the sea.

For the people fortunate enough to live close to the coast, the ocean is even more important. Over 1 billion people depend on the sea as their main source of protein, which explains why overfishing is such a big issue. Besides food, the sea also provides a way to make a living as fishermen, through trade, industry, or tourism (muck diving being only one example). For people living on low islands, rising sea levels are a very real and very large threat. Entire countries might sink below the ocean and will have to move elsewhere. Countries like Tuvalu and Kiribati are already negotiating with Australia about possibilities to move their entire population there. Popular holiday destination Maldives has even gone further and is already buying up land in other countries to prepare for relocating its people.

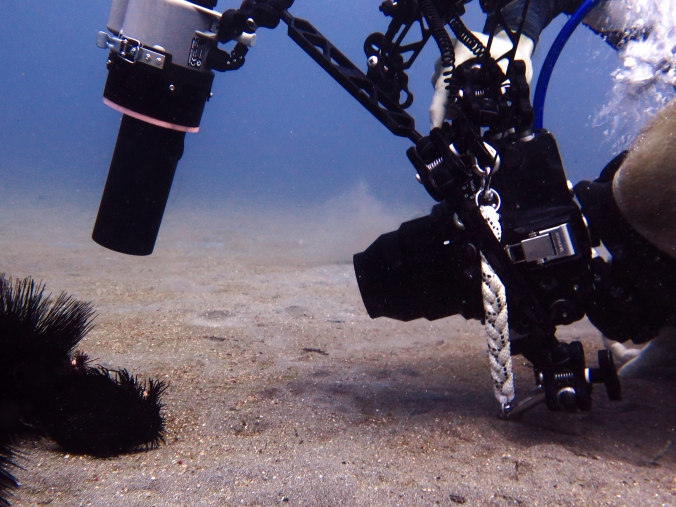

Communicating ocean science is often challenging when people aren’t faced with the ocean in a way the Maldivians or other islanders are. Not being able to see what is below the waves might be the biggest challenge to get people to care about our oceans. It is hard to comprehend just how amazing life in the sea can be without diving in it, or without the help of talented filmmakers and photographers to show us.

Getting your message across in a different way

Getting your message across in a different way

Live scribing at CommOcean

The fact that many scientists are still perceived to live in their “ivory tower of knowledge”, without interacting with people does not help either. The issues facing the oceans are often more complicated than those on land and often seem overwhelming. If the only news people hear about the oceans is bad news, they won’t be keen to listen to the yet another doomsday talk. Most marine scientists are not trained to be communicators and are often too worried about oversimplifying their message, resulting in nuanced, scientifically correct communication that is unfortunately understand by nobody else but scientists. Lastly, in a world where Twitter, Facebook, etc. are increasingly the main source of information for people, it is hard to get attention with a science message. After all, who wants to read about weird fish, if you could be reading about what a Kardashian had for breakfast or that your favourite soccer player went wild on a party last night?

Rita Steyn explaining the ins and outs of Twitter

So what is the solution? How do you get the message across that the oceans matter? I’m in no way an expert, but luckily there were experts around at CommOcean. The first step is to adapt you message to the people you are talking to, don’t go wild on the crazy science talk, have a clear message. (in case you forgot: “Oceans are awesome! Get the news out there!“). Ideally try to interact directly with the people to whom your research is important, stop talking over people’s heads and listen to what they care about. Using social media is a good thing, but do it right and don’t get stuck on just one method. Not everyone uses Twitter or visits websites about science, many people don’t have smartphones and might prefer written media, etc. Don’t forget that humans are visual animals, presenting your message in a more attractive way than dry text will get more attention.

Lastly, maybe most importantly, don’t forget to give the good news. There might be a load of bad news out there, but the ocean is still a beautiful place, something I feel everyone should know about too. Telling people about the beauty that can be found and offering practical tips on how to do something about protecting it can go a long way.

In the long run, what we really need is ocean science to become ingrained in all levels of education. As one of the most important ecosystems in our world, the ocean deserves more attention. After all, as long as people are not aware of the importance of the ocean (and the issues facing it), they cannot change their attitudes about the ocean and they will definitely not change their behaviour to preserve it.

PS: In the spirit of using different communication channels, crittersresearch is now also live on twitter as @DeBrauwerM.

PS: All photos sourced from the CommOcean2016 Facebook page