One of the most important chapters of my research has recently been published in the journal Marine Policy. The paper explains that scuba dive tourism focused on small critters (“muck diving”) has a very high value and how muck diving can be a sustainable alternative to more destructive uses of the environment. This is the link to the paper, but since it is behind a paywall, is rather detailed and perhaps a bit to dry for those of you who are not economists, below is a summary that is easier to digest.

A typical muck diving scene: a sandy bottom with few defining features. In the foreground an Estuary seahorse (Hippocampus kuda) holding on to algae (Photo by Dragos Dumitrescu).

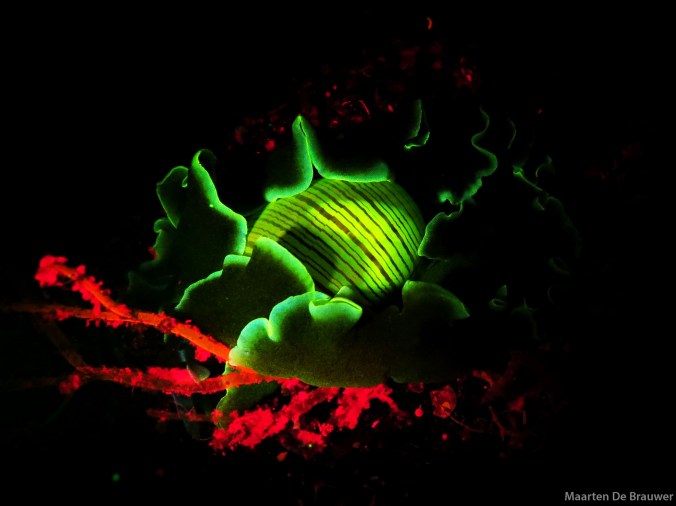

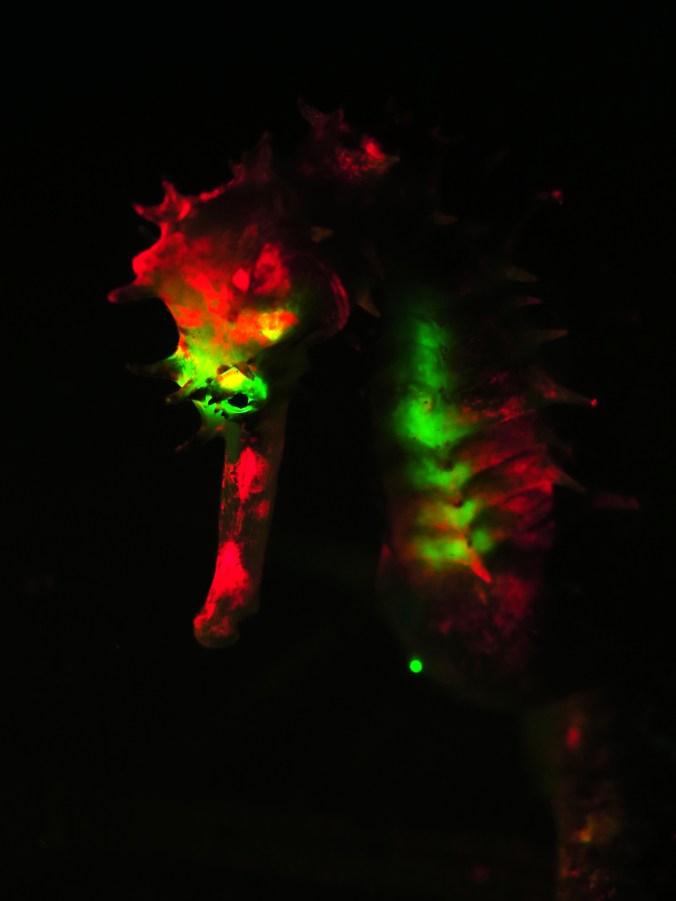

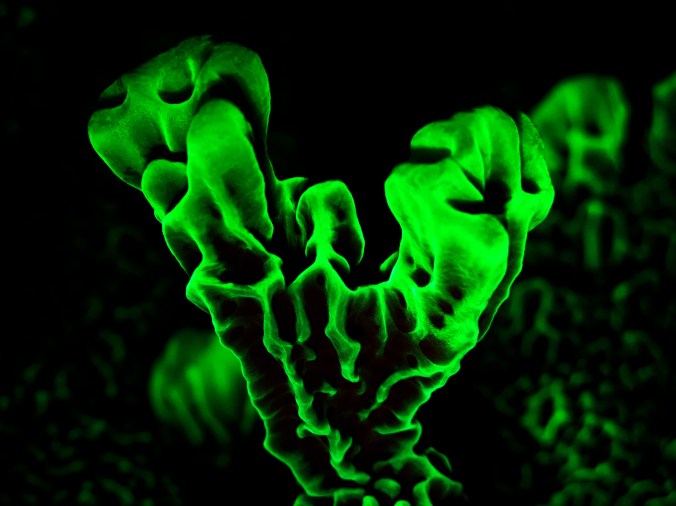

If you don’t know what muck diving is, I invite you to have a look through this site to get a feel for it. But in short: muck diving is scuba diving in sandy areas, usually without coral or other landscape features. The goal is to find weird critters (like flamboyant cuttlefish or hairy frogfish) that you’d rarely see on normal dive sites. It is very popular in places like Lembeh Strait and Dauin in Southeast Asia, but it is done by divers and photographers all over the world.

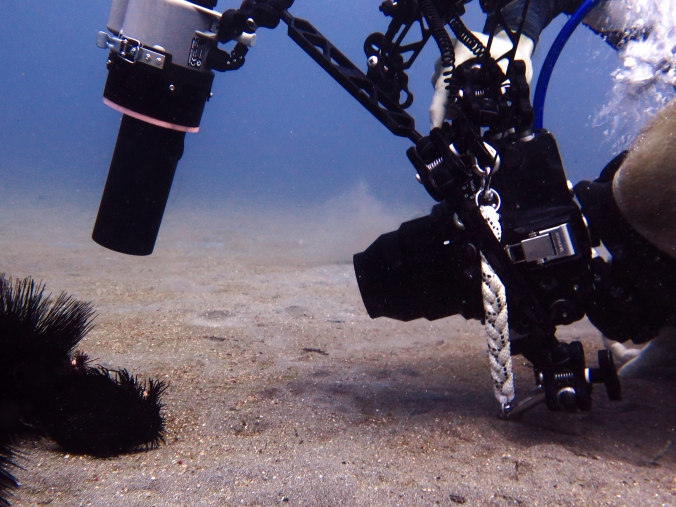

Typical for muck diving is that the people doing it are very experienced, with an average of 580 logged dives. Most of them (73.5%) use underwater cameras, often the expensive dSLR cameras, to photograph all the weirdness down there. Many of the divers are well-educated and have a high yearly incomes. Importantly, most divers would be willing to pay for marine conservation if it benefits the species they come to see.

So what does it matter if some fanatic divers like to spend their holidays rooting through the sand instead of cruising by pretty coral reefs? Well, for starters, those fanatic divers spend a combined whopping $152 million per year in Indonesia and Philippines alone. The real value is probably much higher, as this estimate is only for dive centres that specialise in muck diving, and does not include liveaboards or more general dive centres that visit muck dive sites. The real value could be over $200 million per year! Also bear in mind that this number is for Indonesia and Philippines only, it does not include muck dive tourism in Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, or the rest of the world. With more than 100,000 divers visiting Indonesia and the Philippines to go muck diving, you would expect to get the attention of people managing tourism or ocean resources. Especially since many of the divers said they would not have visited the region, or even the country, if they could not muck dive.

Diver and Ornate ghostpipefish (Solenostomus paradoxus) in Dauin, Philippines

While these numbers might not change anything in your life, they make a huge difference for the thousands of local people that work in this branch of the dive industry. Muck diving is often done in remote locations with limited other forms of income besides fishing. Working as a dive guide and looking at fish is not only more sustainable than catching fish, it also pays a lot better. Roughly $51 million is paid in wages to the local staff working in muck dive tourism annually, and dive guides can earn nearly 3 times more than the minimum wages in the area….

Just stop and think about that for a minute. Imagine the minimum wage in your own country, now triple it. Got the number? OK, now imagine this choice: you can either make that amount by showing cool animals to divers, or you can work your ass off in a factory or risk your life fishing for a third of that amount. Small wonder that many people prefer the first choice, which is great news for marine life in the area, because it means less people fishing and more people trying to protect this valuable source of income.

The future generation of muck dive guides? Not without a healthy ocean (Photo: Luke Gordon)

That is what it comes down to in the end, protecting these extremely interesting and valuable ecosystems. Make no mistake, muck sites can be threatened as well. Coral reefs might bleach because of climate change, mangroves might be cut to make space for shrimp ponds and seagrass might be dredged to mine for sand, but sandy habitats could face other risks with equally bad consequences. All the habitats above receive far more research and conservation attention than the “barren” sandy sites in the tropics. If this paper proves anything, it is that soft sediment habitats have a very high value, and that it should get more attention to avoid loosing amazing biodiversity and the subsequent loss of income for the thousands of people that depend on it.

And that does not even consider loosing that feeling of pure joy when you finally find a critter you’ve dreamed of seeing for years 😉

Muck diving scene: a diver (the science hobbit) taking a picture of a frogfish (black Hairy frogfish – Antennarius striatus)